Food Sources

Best Dietary Sources of Iodine

Iodine rarely makes headlines, but your body relies on it every day. This essential nutrient is needed by the thyroid, a small butterfly-shaped gland in your neck that produces hormones that regulate various aspects of your metabolism, from how fast you burn calories to how fast your heart beats [1]. When iodine intake is adequate, the thyroid can help keep these metabolic processes running smoothly.

For most healthy adults, a daily intake of 150 micrograms of iodine is recommended. Children need somewhat less (90–150 micrograms depending on age), while pregnant women should aim for 220 micrograms and breastfeeding women for 290 micrograms to support their babies' development. [2]

When iodine intake falls short, the thyroid may struggle to function properly. Deficiency can cause problems such as hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, or goiter (an enlarged thyroid). In addition, insufficient iodine during pregnancy or childhood can affect a child's growth and development [2]. On the other hand, getting too much iodine can also be harmful—which is why maintaining a balanced intake, and seeking guidance from a healthcare professional if you're concerned, is important.

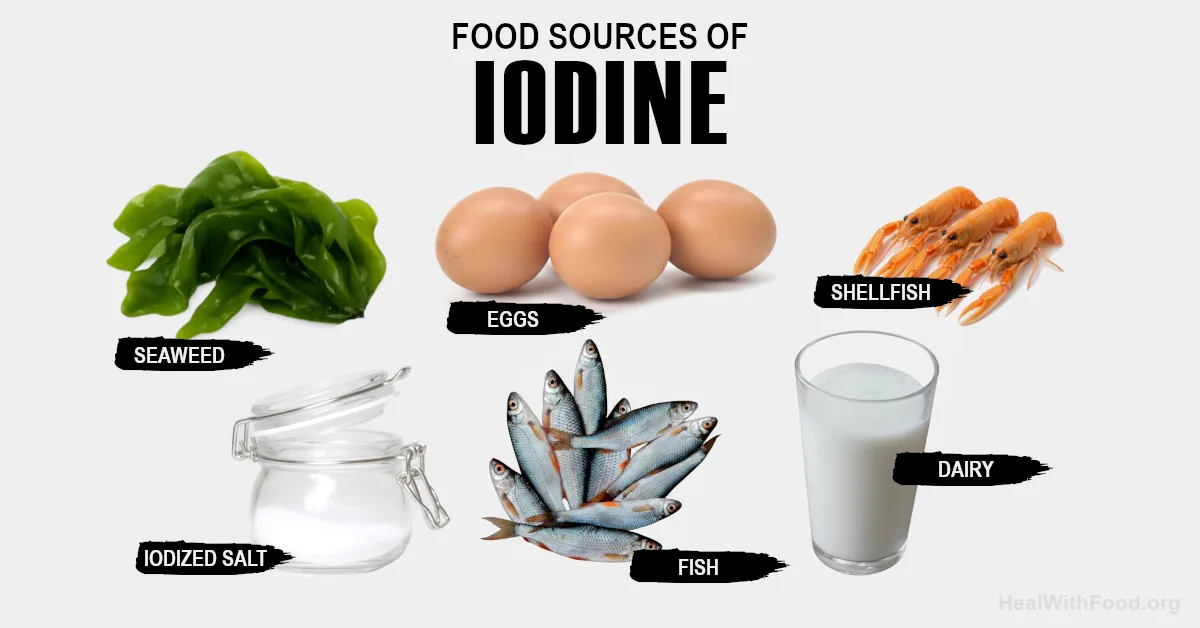

Below, we look at some of the best dietary sources of iodine. Note that the actual iodine levels can vary depending on things like the iodine content of the soil or what the animals ate. That's why the numbers below should be taken as a rough guide, not something set in stone.

Foods Rich in Iodine

Seaweed

Seaweeds can contain extremely high levels of iodine, with the levels ranging from about 1,600 micrograms per 100 grams in nori to over 200,000 micrograms per 100 grams in kelp (aka kombu) [3]. In fact, the most concentrated seaweed sources of iodine contain such high levels that consuming them may pose a risk of iodine toxicity [4, 5].

If you do want to include seaweed in your diet to boost your iodine intake, you might want to choose varieties that are naturally lower in iodine, such as nori, wakame, and dulse.

These options contain much less iodine than kelp, but they are still potent sources of this double-edged nutrient [3], so portion size matters, too. Many packaged seaweed products sold in health food stores include information on their expected iodine content and serving size suggestions which can help you enjoy seaweed safely.

Shellfish

The next group of iodine-rich foods on our list also comes from the ocean—and that's no coincidence. Shellfish such as shrimp, crabs, clams, oysters, and scallops are good sources of iodine largely because of their iodine-rich diets, which include algae and smaller organisms that eat algae.

That said, iodine levels in shellfish vary widely, especially between different species. For example, langoustines have been shown to contain around 342 micrograms per 100 grams, clams about 83 micrograms, farmed Pacific oysters roughly 63 micrograms, and farmed tiger prawns only about 7 micrograms [6].

It's important to note that these numbers are averages, and individual samples can vary considerably depending on factors such as the diet and habitat of the shellfish.

Fish

Moving up the marine food chain, the next group of iodine-rich foods on our list is fish. In general, fish tend to contain less iodine than shellfish, which typically sit lower in the food chain. However, some fish break the rule and are actually excellent sources of iodine. Likewise, not all shellfish are packed with iodine; for example, scallops and prawns contain relatively low levels compared with most fish. [6]

If you like fish and want to boost your iodine intake, haddock is one of richest sources of iodine among commonly consumed fish. The iodine content of haddock has been reported to range from 81 to 910 micrograms per 100 grams, with an average of 427 micrograms [6]. That's a huge spread, which shows why iodine values should be seen as rough guides rather than exact figures.

Still, even the lowest value found for haddock was higher than the highest value measured in many other fish [6], making it stand out as a top natural source of iodine. The flip side is that if you happen to consume haddock from the higher end of that range, you could be exceeding the safe upper limit for iodine.

If you'd rather stick to fish with more moderate amounts, Atlantic cod, pollack and mackerel fit the bill [6].

See Also: Iodine Content of Different Fish (incl. Chart)

Dairy Products

Dairy products are yet another well-known source of iodine, but the amount they contain can vary widely. A review of data from 34 countries found concentrations of iodine in milk ranging from just 5.5 to 49.9 micrograms per 100 grams, with a median of 17.3 micrograms [7].

Much of this variation comes down to what the cows were eating [7]. Farmers often supplement cow feed with minerals such as iodine to support the animals' health. Cows grazing on pasture can also pick up iodine naturally from grass, though the levels in grass fluctuate depending on the iodine content of the soil in that region.

Season also plays a role, with winter milk generally providing more iodine than summer milk. This is because in colder months, cows are usually kept indoors and fed more mineral-fortified feed, which boosts the iodine content of their milk. [7]

Other dairy products such as cheese, yogurt, and ice cream generally reflect the iodine content of the milk used to make them. However, their iodine levels can also be influenced by factors such as the addition of iodized salt as well as production methods.

Eggs

Poultry contains some iodine, but the real hero is the humble egg! Fresh eggs have been reported to contain 27 to 115 micrograms of iodine per 100 grams, with the average at about 49 micrograms [8]. That's a good dose, and since eggs are affordable and widely available across the globe, they make a practical everyday source of iodine for millions of people.

Just one thing: if you're planning to boost your iodine intake with eggs, be sure to eat the whole egg—or at least not skip the yolk—as over 90 percent of an egg's iodine can be concentrated in the yolk [9]!

Foods That Contain Iodized Salt

One challenge with the foods we've covered so far is that their iodine contents can vary a lot. That makes it hard to estimate exactly how much iodine you're getting from seafood, dairy, or eggs.

This is where iodized salt comes in. In many countries, table salt is fortified with a specific amount of iodine to help prevent widespread iodine deficiency. This practice dates back to the 1920s, when governments around the world began introducing salt iodization programs. The first country to do so was Switzerland, a mountainous country with iodine-poor soils and historically high rates of goiter and cretinism—both linked to iodine deficiency. [10]

Today, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that iodized salt contain 14–65 milligrams of iodine per kilogram, depending on a country's average salt intake [11]. In the U.S., the standard is 45 milligrams per kilogram, and salt labeled "iodized" on store shelves generally meets this target [2].

In practical terms, the U.S. standard of 45 mg per kilogram means that just two-thirds of a teaspoon of iodized salt delivers roughly 150 micrograms of iodine—the full daily recommendation for most adults.

Now that doesn't necessarily mean you should make it a habit to add two-thirds of a teaspoon of iodized salt to your home-cooked meals every day. That's because you're probably getting salt from other sources as well, and too much salt isn't good for you. In fact, the American Heart Association (AHA) recommends a total sodium intake of no more than 1,500 milligrams per day for most adults [12], which is equivalent to roughly two-thirds of a teaspoon of salt. That total includes all sources of sodium, including the iodized or non-iodized salt you add to your home-cooked meals but also the large amounts that come from processed foods.

Also, getting the recommended amounts of salt from a variety of foods, including processed foods, doesn't automatically mean that your iodine needs are met. That's because in the U.S., most processed foods are made with non-iodized salt [13], so their salt contributes sodium but little to no iodine.

The Takeaway

The levels of iodine in foods like seafood, dairy, and eggs can vary a lot from serving to serving. Iodized salt, on the other hand, delivers a much more predictable amount.

The catch is that for most Americans, relying only on iodized salt would probably mean taking in more sodium than health experts recommend.

That's why it makes sense to get your iodine from a mix of sources: a pinch of iodized salt in your cooking, plus naturally iodine-rich foods like seafood, dairy, and eggs. Together, they can help cover your needs without overloading on salt.

References

- The Ohio State University. Thyroid Gland. Last accessed: September 2025.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH), Office of Dietary Supplements. Iodine (Fact Sheet for Health Professionals). Last accessed: September 2025.

- Teas J, et al (2004). .Variability of iodine content in common commercially available edible seaweeds. Thyroid, 14(10):836–841.

- Smyth PPA (2021). Iodine, Seaweed, and the Thyroid. European Thyroid Journal, 10(2):101-108.

- Blikra MJ, et al (2024). Exposure to iodine, essential and non-essential trace elements through seaweed consumption. Sci Rep, 14:11962.

- Sprague M, Chau TC, Givens DI (2022). Iodine Content of Wild and Farmed Seafood and Its Estimated Contribution to UK Dietary Iodine Intake, The Supplement. Nutrients, 14(1), 195.

- Tattersall JK, Bath SC, van der Reijden OL, et al (2024). Variation in milk-iodine concentration around the world. Food Chemistry, 437:137960.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (2024). USDA, FDA and ODS-NIH Database for the Iodine Content of Common Foods. Release 4.0.

- J. Travnicek et al (2006). Iodine content in consumer hen eggs. Veterinarni Medicina, 51, 2006 (3): 93–100.

- Swiss Academies of Arts and Sciences. Iodised salt. Last accessed: September 2025.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guideline: Fortification of food-grade salt with iodine for the prevention and control of iodine deficiency disorders. October 20, 2014.

- American Heart Association (AHA). How Much Sodium Should I Eat Per Day?. Last Reviewed: Jul 15, 2025.

- A. Leung (2012). History of U.S. Iodine Fortification and Supplementation. Nutrients, 4(11):1740–1746.